Post boxes and Power in Jerusalem

The Austrian post box was a dark royal blue with gold trim. It was also considerably larger than its main rival in the yellow German post box, an interesting admission by the Germans at lacking the same quantity of trade as the Austrians. This confession of inferiority was offset by flaunting its nationality through the strong contrast between the yellow of the box and the black German imperial crest. The French post box was the same colour as the Austrian but distinguished itself by its curious shape- a much smaller box sat on top of a post of the same colour. The Ottoman postal service made no attempt to engage in this posturing competition among European powers for the postal trade in Jerusalem. It settled for a plain wooden box.

It may be somewhat ludicrous that the most powerful countries in the nineteenth century competed for influence in Jerusalem through the colour and size of their post box. Nevertheless postal services offered the opportunity to make revenue in a land lacking in natural resources. The Ottoman postal service had barely existed for inland cities like Jerusalem, before its reform in 1840, and the first European postal services obtained permits to trade in the empire in 1837.

So the Europeans entered the scene at the same time as the reach of the Ottoman government was extending into places that had rested easily within the empire without engaging much with it. The Ottoman and the various European postal services therefore were competing for revenue but also influence. A postal office in Jerusalem offered access to local merchants. It was an easy step from delivering the post to arranging commercial contracts to transport goods to Europe. Indeed the Austrian postal service began life as a shipping company for goods in the Mediterranean. There was also the influence that came from branding. Locals in Jerusalem regularly handling your stamp eased the way into their familiarity with you – a crucial asset for a European power eager for authority in an empire on its last legs. A rivalry via the colour of post boxes may conjure up a somewhat twee image but this rivalry was a reflection of a contest for the power that comes from transporting information.

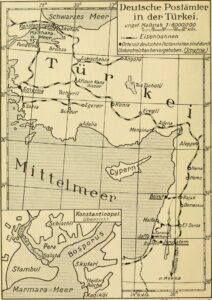

GERMAN POST OFFICES IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE

The post box was the equivalent of Huawei offering 5G- the technical innovation by a rising power to disrupt a game dominated by existing powers. The Austrian and the French postal services had acquired permission to trade in the major Ottoman cities in 1837, the Russians in 1856 but the Germans took until 1898 (the British red post box did eventually make an appearance but not until after World War One). The Germans’ intention was to offer an easier customer experience: it was more convenient to use a post box than travel to the post office. The Austrians responded by upping their offer- arranging exclusive deals with local communities for free postal services within Ottoman lands in return for exclusive use of the Austrian service for post to Europe.

The great power rivalry could only operate in cooperation with local communities, much like how the US could not prevent the British government agreeing for Huawei to provide 5G. This was as true for commercial power and postal services as for religious power and constructing monumental buildings. After all you need efficient transport in order to offer efficient postal services and to transport stone for buildings. The opening of a railway from Jaffa to Jerusalem was the culmination of fifty years of improved links between Jerusalem and the coast. The bank that financed the building of a railway from Jaffa to Jerusalem was the Jacob Valero Bank. The Valeros were a Jewish family of Middle Eastern origin and they founded the first bank in Jerusalem in 1848. They were local and regularly loaned money to the Ottoman governor in Jerusalem and so they were able to finance the railway. Indeed this bank has underpinned many of the developments discussed in this series on the history of Jerusalem. It financed the building of the Prince Sergei Hostel in the Russian Quarter and several other buildings, it handled the money for Kaiser Wilhelm’s grand entrance into Jerusalem in 1898, it transferred the donations of Moses Montefiore, the Rothschilds and other Jewish philanthropists to the Jewish building projects, it offered loans to the Arab notable families for their pleasure palaces.

The Valero Bank is an example of the sort of local initiative in Jerusalem that enabled European development in the city. Many of these initiatives began in the 1830s, before the European arrival, as local Muslims, Christians and Jews responded to the capture of Jerusalem by the Egyptian army. Many of these initiatives were self-consciously ‘modern’, in the sense of developing Jerusalem and working across religious and cultural divides. The clerk at the Valero Bank ‘was extended great importance both within and without the bank. Both Jewish and non-Jewish clerks were like young consuls, their walk was like “the walk of princes.” They strolled in elegant suits and shiny shoes. Gold watches hung from their vests and they held handsome canes in their hands.’ These local institutions sought to integrate the population of Jerusalem, even if it was in pursuit of profit. The Europeans instead tried to create their own spheres of influence, centred on particular religious communities.

CHAIM VALERO, DIRECTOR OF THE VALERO BANK

Those yellow German post boxes signalled the end though for many of these institutions. Kaiser Wilhelm’s visit to Jerusalem in 1898 intensified the European competition in Jerusalem. The Austrian and the French postal services did not take lightly to German attempts to steal their custom. It was no longer enough to maintain a sleepy post office. Jerusalem was developing, there were greater profits to be made and local institutions were not going to get in the war.The railway that the Valero Bank had financed now became the bank’s downfall as European banks rushed into Jerusalem with their huge financial firepower. The Valero Bank was forced to close in 1915, unable to compete.

The post boxes and the Valero Bank illustrate the overall story of this series. It is a story of a rapid multiplication of power centres in Jerusalem. The Egyptian capture and rule of Jerusalem in the 1830s drew the European powers to Jerusalem and sparked local institutions into life. The Ottoman recapture of the city in 1840 brought a new, more intrusive form of Ottoman government. In the space of ten years, the locals of Jerusalem suddenly enjoyed access to a variety of sources of power which offered services whether that be banking, immunity from Ottoman laws, the opportunity to make money, the chance to strength one’s position in religious disputes. These sources of power developed Jerusalem from a backwater town into a major city. No source of power was able to exclude the others and so they had to compete with the means available to them. This meant for the Europeans competing through sponsoring religious communities and constructing monumental buildings. The Germans injected a new energy into this competition, putting strain on the flourishing integrated culture of the city. The development of Jewish communities along Jaffa Road tested further this culture by creating rivalry around the use of holy sites. Nevertheless a new Jerusalem had come into being on the eve of World War One, a flourishing city of common public spaces: cafes, theatres, literary societies.

That war devastated the city but it also led to a far more significant development for Jerusalem. The war forced Britain to rethink its system for defending its empire. The idea was born that Britain needed to be the prime source of power in Jerusalem and across the Middle East. In 1917 General Allenby captured Jerusalem from the Ottomans, beginning a new period in the history of the city. Britain would try to exclude all other sources of power in Jerusalem and so set the conditions for the next thirty years of Jerusalem’s history.